The best place to stand for a sense of Yellowknife is beside the Bush Pilot’s Monument at the top of the Rock. The six-storey “volcanic pillow” formed when lava surged up through the earth, creating the perfect vantage point on which to erect a tribute to the pilots who risked their lives ferrying people and supplies around the North.

And when you’re standing on the Rock, the best person to stand next to is Mike Kalnay, who has an encyclopedic knowledge of Yellowknife’s history and inhabitants. He trained as an architect, came to Yellowknife 31 years ago as a politician, became a subarctic food forager (moss, fireweed, birch sap) and now works as a guide for My Backyard Tours. “You get to do all sorts of stuff when you live up here,” he says.The best place to stand for a sense of Yellowknife is beside the Bush Pilot’s Monument at the top of the Rock. The six-storey “volcanic pillow” formed when lava surged up through the earth, creating the perfect vantage point on which to erect a tribute to the pilots who risked their lives ferrying people and supplies around the North.

And when you’re standing on the Rock, the best person to stand next to is Mike Kalnay, who has an encyclopedic knowledge of Yellowknife’s history and inhabitants. He trained as an architect, came to Yellowknife 31 years ago as a politician, became a subarctic food forager (moss, fireweed, birch sap) and now works as a guide for My Backyard Tours. “You get to do all sorts of stuff when you live up here,” he says.

I don’t normally take tours when I travel, but Yellowknife is different — its idiosyncrasies are best experienced with a local by your side. As Kalnay and I gaze down from the Rock over Great Slave Lake and the eclectic jumble of houses, shacks and cabins that jut out of the chunk of Canadian Shield that is Old Town, he tells me how, from January to March, there are more ice roads (speed limit 50 km/h) than “road” roads in Yellowknife. “Of course,” he adds, “people around here have a habit of bypassing the city’s road barriers as early as December.”

A tendency to disobey traffic rules is just one way the people here have preserved a feeling of irreverent frontier rebelliousness in the capital of the Northwest Territories.

Take, for instance, the community of cheerfully painted houseboats that bob defiantly on the bay below us. The inhabitants, also known, usually affectionately, as “water squatters,” don’t pay municipal taxes because, technically, they’re not on municipal lands.

And when you wander the crooked streets of Old Town, you’ll eventually find yourself in another off-the-grid, non-tax-paying neighbourhood: The Woodyard, where a diverse group of people, from business owners to mine workers, have built homes out of whatever they could find, including a school bus.

Old Town’s colourful community is also known for its many murals — even the dumpsters serve as backdrops for paintings — and unusual street names, like Ragged Ass Road, made famous by Tom Cochrane. (The chamber of commerce began selling “Ragged Ass Road” street signs so tourists would stop stealing them.)

Kalnay wants to continue our history lesson at the Legislative Assembly, where nine original A.Y. Jackson paintings hang in “the room of no secrets,” acoustically designed so you can hear the faintest whisper from anywhere in it. But first, it’s time to stop for tea.

We meet Carmen Braden, an award-winning composer and musician, and her father Bill Braden, a photographer and author, in her office, where we sip tea from music-themed mugs. The conversation flits from art to politics to family and, eventually, to the misconceptions people have about Yellowknife.

“People think it’s empty and hard to get to,” Bill laughs. “It’s just this pink part of the map.” Carmen is determined to prove otherwise, and to “open people’s eyes to the beauty around Yellowknife.”

A few years ago, she recorded the sounds of the ice on the lakes around the city and, in 2015, released “The Ice Seasons,” a 25-minute composition that “evokes the beauty and behaviour of subarctic ice.” Carmen says the experience was both poetic and scientific — and she couldn’t have done it anywhere else. “Something about the space up here gives you the freedom to do your own thing.”

In 2019, Carmen launched the Longshadow Music Festival to celebrate Canadian music and, last summer, held the festival at Sundog Trading Post, a large log cabin in Old Town owned by Richard McIntosh and Christine Wenman, who also happen to be houseboaters.

The couple offer a houseboat tour along with hiking, birding, fishing and kicksledding, and plan to turn Sundog into a one-stop cultural and recreational hub. (It’s also a café featuring homemade ice cream in 10 flavours, including cinnamon streusel.)

No trip to Yellowknife is complete if you don’t get out on the water, so I join McIntosh for a motorboat tour of the houseboats in the bay. He tells me the “twists and turns of life” brought him to Yellowknife, but that houseboat living is where it’s at. Theirs is a cosy 900 square feet with three rooms, shared with their two young children and two cats.

The hardest part of living on a houseboat is the extra chores, like cutting wood for the stove, McIntosh says. Getting around can be tricky, too. When the ice is unreliable, they use a canoe — one foot in, one foot out — to skid to shore, hopping in at the first sound of a crack.

But there are also perks. “We live with the great outdoors at our front door,” he says. “During the summer we explore the lake by boat, and in the winter we have instant access to an outdoor hockey rink.” And from late summer to early spring, they also have the best skies for viewing the aurora borealis.

On my first aurora tour, I’m rewarded with a spectacular sky, dancing and shifting in green and purple. In my head, I know it has something to do with sunspots, space dust and solar winds, but in my heart, it’s pure magic.

My second trip out, the weather isn’t as co-operative, but it doesn’t matter because this time I’m warmly ensconced in Tracy Therrien’s cabin, sipping tea and watching her make a “midnight lunch” of fish chowder and hot-from-the-oven bannock. Therrien is part Cree and created Bucket List Tour in 2011, partly to share her Indigenous knowledge and history. About 24 per cent of Yellowknife’s residents are Indigenous.

Therrien says the most common invitation to an Indigenous home here is for tea and bannock. “It was important for me to include that because, if the aurora doesn’t visit, I still want my guests to leave with a memorable evening.”

It is memorable. And as I sit listening to her stories about brushes with bears and the best way to make bannock, I’m glad it’s raining. Like every part of my trip to Yellowknife, it’s the people I meet, and the wonderful tales they tell, that make me realize this culturally rich, delightfully unconventional city is like nowhere else on Earth.

Sydney Loney travelled as a guest of Destination Canada and Northwest Territories Tourism, which did not review or approve this article.

If you go

How to get there: In May, Air North launched the first direct, scheduled service from Toronto to Yellowknife (about five hours), which will operate seasonally. WestJet Encore also flies into Yellowknife from Calgary year-round.

Where to stay: The Explorer Hotel is walking distance from Old Town, and you may just find yourself in the royal suite where Queen Elizabeth II, King Charles and Prince William and Princess Catherine have all stayed.

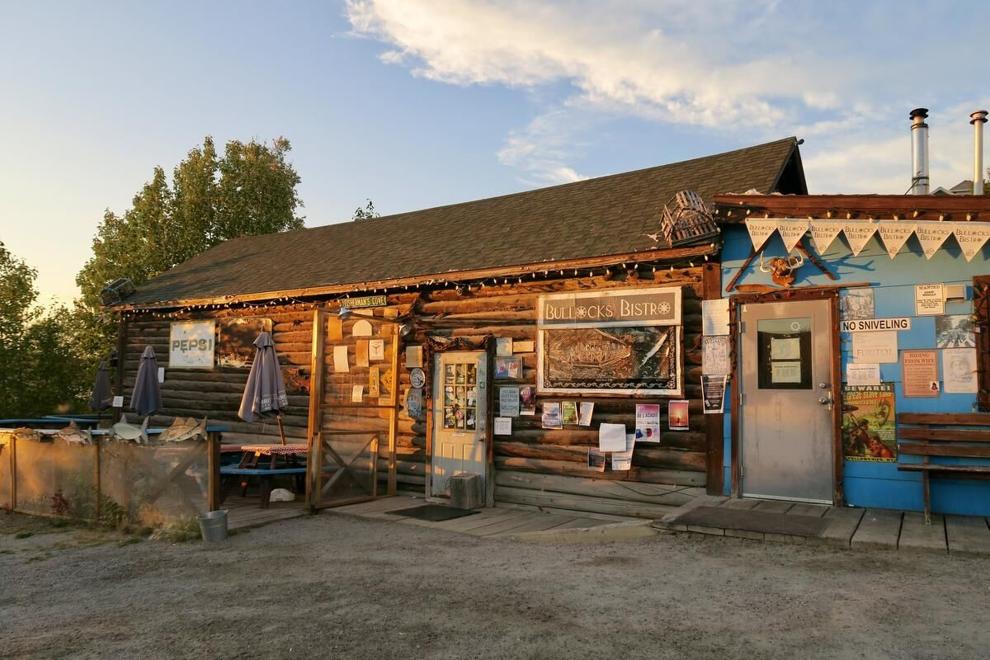

Where to dine: Bullocks Bistro is where locals go for catches fresh from the lake — it’s especially famous for its fish and chips. The small room’s rough wooden walls are covered with the signatures and memorabilia of diners past.